Exploring the Office 365 Substrate

Things Were Different in 2011

When Microsoft launched Office 365 in June 2011, the suite included a set of cloudified on-premises applications that were barely on nodding terms with each other connected with a nascent Office 365 infrastructure. Over time, the service has grown to support over 200 million monthly active users. More importantly, Office 365 is now a more integrated, better connected, coherent whole. The boundaries that once existed between applications like Exchange and SharePoint have largely disappeared in the interests of the service.

Some impressive software engineering has been done to make Office 365 the way it is today. The telemetry signals gathered in the Microsoft Graph is a huge part of enabling the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning in current applications.

Snover Sparks a Thought

Another key component in the story is the Office 365 substrate, a poorly-understood part of how things work across the service. During a Microsoft Mechanics show taped at the Microsoft Ignite 2019 conference, Jeffrey Snover, Microsoft Technical Fellow and Architect for the Intelligent Substrate Platform in Office 365, presented how things connect within the service. He said that the substrate, “a set of storage and a set of services”, was the “heart of Office 365.” The services are for “creating, collaborating, and communicating” and “everything gets stored in the substrate or has a digital twin (copy) in the substrate.” Collectively, the substrate enables Office 365 a “planetary scale people operating system.”

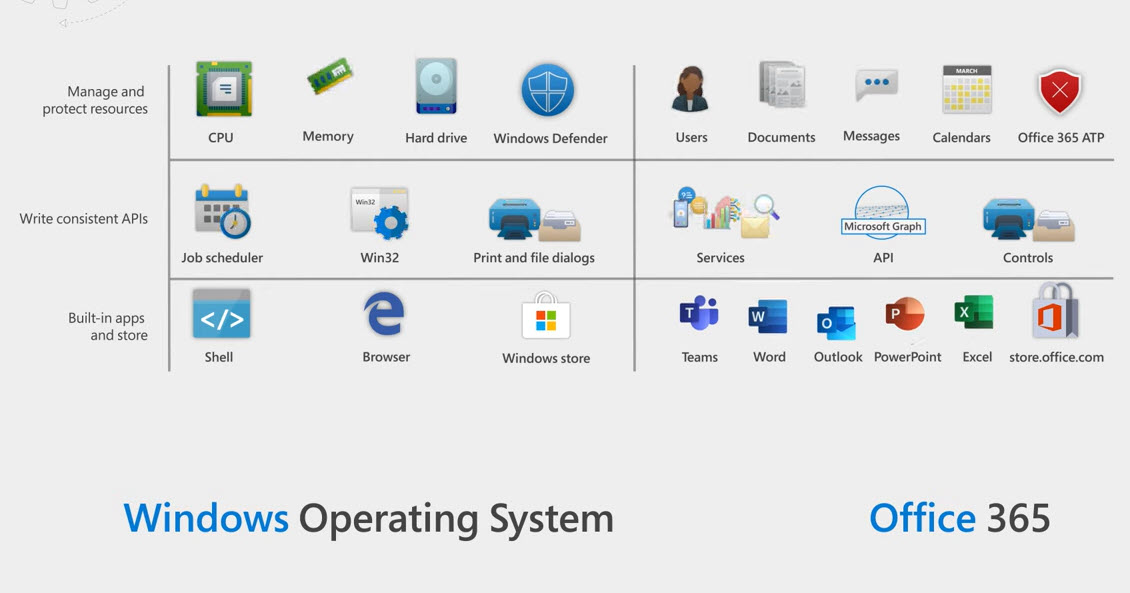

Snover presented a comparison between traditional operating systems like Windows and Office 365, noting that both provide ways to manage and protect resources, consistent interfaces, and some built-in apps (Figure 1).

Interpreting the Office 365 Substrate

I was taken by the thought and decided to come up with my own view. Because I am not a Microsoft employee, my view is different to Jeffery’s, but there’s no harm in that.

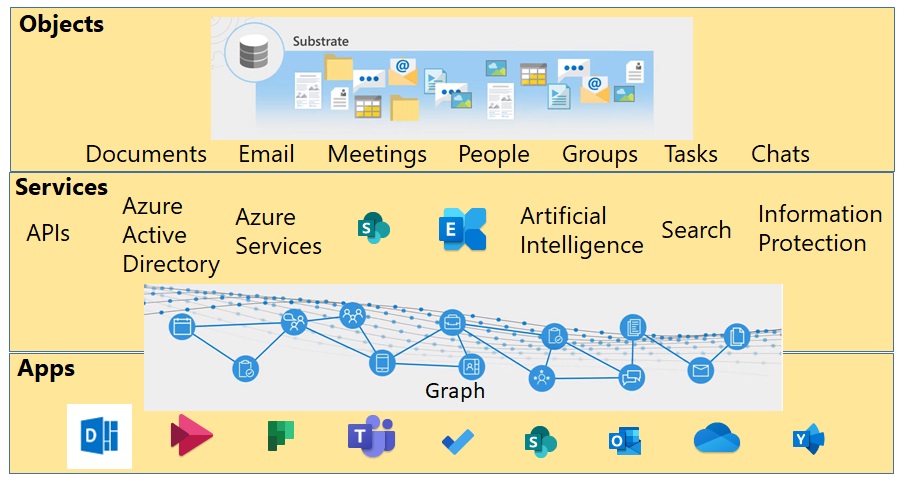

Dictionaries offer several definitions for substrate. One that seems appropriate for this discussion is that a substrate is an underlying substance or layer. Viewing Jeffrey’s take on Office 365 as an operating system through my own lens, I came up with Figure 2.

Objects and Interfaces

Objects are easy to understand. They’re the individual items of data that people work with stored in different repositories that we don’t need to worry too much about. At least, not in the same sense that on-premises become concerned about databases and other files because Microsoft manages the repositories in the cloud. Knowing that SharePoint Online stores documents and lists in Azure SQL or that Teams uses Cosmos DB is interesting but not essential. Collectively, the set of objects in Office 365 forms the substrate.

Services are a set of connecting technologies that tie data drawn from across Office 365 together. Notice that I include Exchange Online and SharePoint Online here. That’s because these two basic Office 365 workloads deliver services to many applications. For example, Exchange Online stores compliance records for Teams (and soon Yammer). SharePoint Online delivers document management to Teams, and so on.

APIs tied to individual applications are dying out and being replaced by Graph endpoints. Because so many third-party and customer apps use the older APIs this process will take time, and perhaps much longer than people imagine. But it will happen.

The Human Side of Office 365

Apps are the human side of Office 365 and are what people interact with daily. Apps are more mobile and more intelligent as they consume more of the signals available in the Graph. Early examples of machine learning, like Outlook’s Focused Inbox, will seem very crude in the future as more artificial intelligence is applied across Office 365.

Diving into the Office 365 Substrate

Some years ago, it was noticed that Exchange Online mailboxes had a Files folder which stored copies of documents. This was one of the first signs of the substrate in action. Essentially, Office 365 now uses Exchange Online mailboxes to hold much more than personal email. Items drawn from across Office 365 are in mailboxes. Some are copies of items like documents from SharePoint Online and OneDrive for Business sites; some are the original data.

What’s happening is that Exchange Online mailbox databases have become the physical implementation of the Office 365 substrate. Bringing data together in one place makes it easier for common services like Search to work. This doesn’t mean that apps like SharePoint Online and Teams have lost their repositories; it does mean that “digital twins” of items exist in multiple locations.

It might seem surprising that Exchange Online databases serve in this role, but the Exchange database engine (ESE) has always been good at managing many different types of data, can scale up efficiently, and runs on lost-cost storage. In addition, the Exchange Online Native Data Protection model makes sure that each item is copied to four databases, including a lagged database, to ensure robust data availability. ESE also supports “sharding,” the ability to connect different chunks of data into a logical whole (for instance, 50 GB mailboxes are combined to form expandable archives), which makes it easy to present data on a per-user or per-tenant basis.

The substrate is the essential foundation for what Office 365 is today. Without the substrate, apps couldn’t get to data as easily as they can. Apps couldn’t integrate with each other or with other services as easily as they now can, nor would it be possible to envisage how apps might integrate in the future using the Fluid Framework. And without the substrate, Office 365 would look like that collection of loosely cloudified on-premises products from 2011.

Rationalization Within Office 365

The growing cohesion of Office 365 and the existence of the substrate encourages rationalization of engineering effort and improvement in user functionality. For instance, Teams is soon to get a new Tasks app. The task items are shared with To Do (which powers Outlook tasks) and Planner in stored in the substrate. Each app puts its own unique spin on how people process tasks, but the underlying data is consistent and can therefore be surfaced in and shared by the different apps. And in January 2020, when the Office apps gain the ability to create tasks, those items will be in the same data store powered by the Office 365 substrate.

Although Microsoft is making good progress in rationalization across Office 365, it wasn’t always so. Yammer is the poster child of do it yourself technology inside Office 365. After Microsoft bought Yammer in 2012, the opportunity existed for Yammer to adopt Microsoft technology to improve its integration with the rest of the service. For example, Yammer could have switched its database for either ESE or SQL. That didn’t happen, and Yammer remained as an outlier until it started to connect with Office 365 Groups in 2016. Had Yammer switched databases a few years ago, it might not have the problems with eDiscovery, compliance, and data governance that Yammer is only just starting to deal with.

Rationalization within Office 365 makes sense from an engineering perspective. It’s also good for business. Engineers have fewer moving parts to deal with; interfaces become more consistent; and people are more productive. Software should be more predictable and higher quality too, at least in theory.

Hidden from View

The best thing about the Office 365 substrate is that tenants don’t have to worry about it. Just like we shouldn’t care about what database Microsoft selects for its next cloud app, we shouldn’t need to know much about the substrate. Just think of the substrate as the power network for Office 365, connecting data to apps. End of story.